Eddie Palmieri: The Architect of Latin Jazz Power

The Sound of a City

There are artists who shape a genre—and then some shape culture. Eddie Palmieri, who passed away at the age of 88, was not just a giant of Latin jazz. He was a movement unto himself. A pianist, composer, bandleader, philosopher, innovator, and iconoclast, Palmieri forged a career that defied boundaries and defined eras. From the streets of Spanish Harlem to the world’s grandest stages, he created a body of work that fused rhythm with resistance, soul with scholarship, and joy with justice.

The first time I heard Eddie Palmieri, I didn’t fully understand what I was listening to. I felt it more than I heard it. His music didn’t enter politely through the ears—it shook the floor under your feet. It was the sound of claves cracking like lightning, of trombones charging like bulls, of piano lines that refused to behave. It was spiritual, subversive, and streetwise all at once.Palmieri’s music didn’t just reflect the pulse of New York’s barrios—it helped define them. It gave voice to an urban Latino experience too often overlooked by the mainstream. He carried forward African and Caribbean traditions, reshaped them through a jazz lens, and added his own bold signature: the thunder of the left hand, the fury of dissonance, the surprise of silence. He didn’t ask permission. He declared his presence.

Chapter 1: Born of Bloodlines and the Bronx

Eddie Palmieri was born on December 15, 1936, in Spanish Harlem, New York, to Puerto Rican parents who had emigrated during the wave of Caribbean migration in the 1920s. Raised in the Bronx, Eddie grew up in a household immersed in music. His older brother, Charlie Palmieri, was already a prodigy—by the 1950s, Charlie would be known as “The Giant of the Keyboards,” a figure of immense stature in Latin music circles. It was Charlie who first introduced Eddie to the piano.

Their household was a place where classical training met Caribbean heritage. The family prized education, and Eddie began formal piano studies at a young age. But in the streets and clubs outside his window, the soundtrack was Afro-Cuban—mambo, son, rumba, and guaguancó. Young Eddie soaked it all in.

At 13, he was performing with his uncle’s band, learning the trade the old-school way: gigging, hustling, absorbing. While still in his teens, he worked with respected leaders like Vicentico Valdés and Tito Rodriguez, gaining on-the-ground experience that would shape his approach to bandleading. And though his early musical diet included Chopin, Beethoven, and Mozart, Eddie was also drawn to the modern jazz revolution—he admired Bud Powell’s complexity, Thelonious Monk’s angularity, and the harmonic sophistication of Bill Evans.

This duality—of roots and rebellion—became a cornerstone of his artistry.

Chapter 2: La Perfecta and the Birth of a New Sound

In 1961, Palmieri broke from convention and launched his own band: La Perfecta. It was anything but traditional.

Instead of the standard Latin ensemble lineup that leaned heavily on trumpets or saxophones, Palmieri constructed a frontline of two trombones, adding a rougher, deeper tonal grit to the sound. The result was unlike anything audiences had heard before—massive, bold, sonorous, and almost orchestral in its depth. The brass didn't glide; it punched. The rhythm section didn’t just support; it surged.

La Perfecta’s early recordings—La Perfecta (1962), El Molestoso (1963), and Lo Que Traigo Es Sabroso (1964)—set off a quiet revolution. Tracks like “Azucar” and “Mi Congo” were more than dancefloor bangers; they were blueprints for a new Latin jazz architecture. Palmieri blended Cuban rhythms with modal jazz harmonies, extended improvisations, and blistering arrangements that owed as much to John Coltrane as to Arsenio Rodríguez.

He created a language that bridged continents—an Afro-Caribbean heart with a jazz head and a New York attitude.

Palmieri was also one of the first Latin artists to seriously center the pianist as a lead soloist in a genre where percussion and brass often took top billing. His montunos (the repetitive piano vamps central to Cuban-derived music) were rarely just functional—they were kinetic, dynamic, exploratory. He would layer clusters of dissonance, stretch timing, shift accents, and build tension like a jazz pianist sculpting a solo in real time. His left hand thundered, his right hand danced.

Chapter 3: Innovation in the Age of Revolution

The 1960s and ’70s were fertile ground for Eddie Palmieri’s most radical and politically charged work. While his contemporaries were refining salsa as a commercial form, Palmieri was deepening the art form’s emotional and intellectual reach.

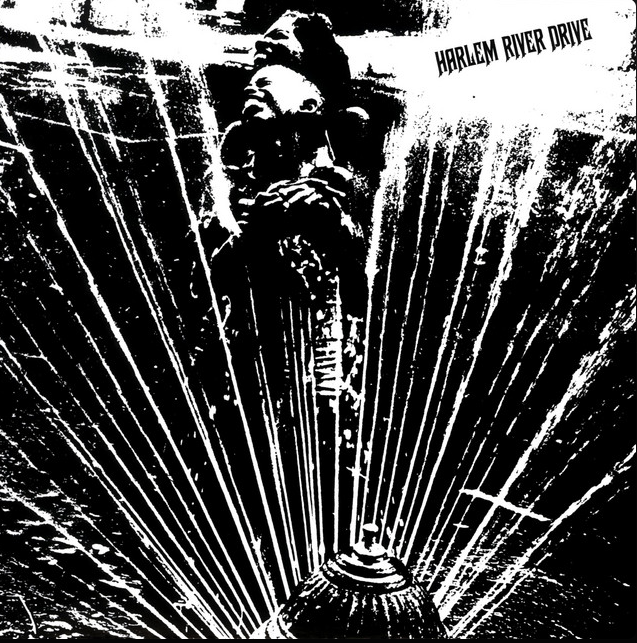

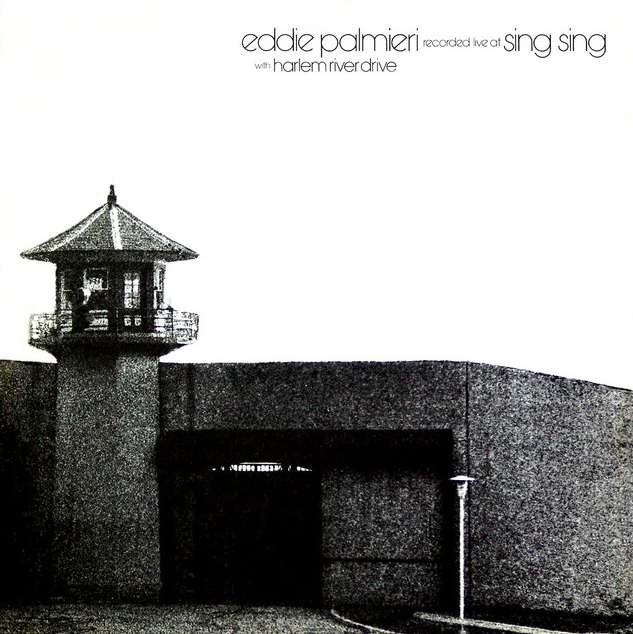

In 1968, he released Champagne, a bold and at times psychedelic work that foreshadowed the experimentation to come. But it was 1971’s Harlem River Drive that cemented his status as a revolutionary.

Part jazz-funk, part soul, part urban street sermon, Harlem River Drive brought together Black and Latino musicians in a project that addressed poverty, inequality, and systemic neglect. The title track is an urgent call-to-action—a polyrhythmic storm underscored by lyrics like “What you got is not enough.” It wasn’t just music. It was protest. It was power.

That same year, Palmieri dropped another masterwork: Vámonos Pa’l Monte (“Let’s Go to the Mountain”). The album, especially its title track, became an anthem—equal parts escape fantasy and coded resistance. In the middle of social unrest, Vietnam, and political upheaval, Palmieri’s music offered both critique and comfort.

This was also the period in which he collaborated with some of the finest musicians of his career—conguero Mongo Santamaría, trombonist Barry Rogers, vocalist Ismael Quintana, and bassist Andy González, to name a few. The musical chemistry was undeniable. The records burned with intensity.

Throughout these years, Palmieri’s music expanded—not just in personnel but in scope. He would often compose extended suites, incorporating Afro-Cuban religious rhythms, jazz counterpoint, and thematic storytelling. Albums like Justicia (1969), Unfinished Masterpiece (1974), and The Sun of Latin Music (1974) didn’t just win awards—they reshaped what was possible in Latin jazz.

Palmieri wasn’t interested in crossover appeal or industry formulas. He was interested in truth. And truth, in his hands, came with clave and consequence.

Chapter 4: Grammy Gold and Global Recognition took time,

Eventually the industry caught up with Eddie Palmieri’s genius. In 1975, he made history by becoming the first Latin artist to win a Grammy in the newly created category of Best Latin Recording. The winning album, The Sun of Latin Music, was a tour de force—equal parts Afro-Caribbean ritual, jazz improvisation, and orchestral experimentation. It cemented his place not only as a pioneering Latin musician but as a genre-defying composer whose work deserved recognition at the highest levels.

Palmieri didn’t just win a token Grammy. He went on to win ten over the course of his career, more than any other Latin jazz artist of his generation. Albums like Unfinished Masterpiece, Palo Pa’ Rumba, Obra Maestra (with Tito Puente), and Palmas all received the industry’s top honours. But behind every award was a deeper truth: that Eddie Palmieri never compromised.

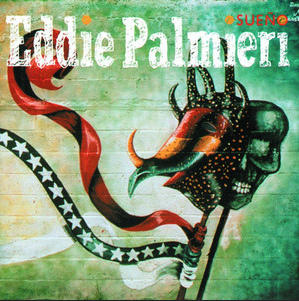

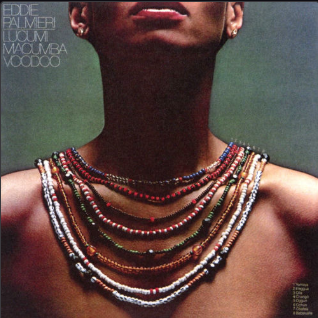

While others bent toward commercial salsa formulas, Palmieri leaned further into experimentation. Lucumi, Macumba, Voodoo (1978) was a spiritual jazz journey steeped in Afro-Cuban religion and mysticism. Palmas (1994) was as dense and complex as anything from the ECM or Blue Note jazz catalogs. Listen Here! (2005), featuring Michael Brecker, Regina Carter, and Nicholas Payton, placed Palmieri at the intersection of Latin jazz and modern swing, proving—at nearly 70—that he could still break new ground.

He played major festivals, packed out auditoriums across Europe and the Americas, and became one of the most respected elder statesmen of Afro-Caribbean music. Yet through it all, Palmieri never forgot his roots. He remained a Bronx boy at heart, a barrio intellectual whose success only deepened his sense of responsibility to the communities that raised him.

In his speeches, he spoke of structural inequality. In his liner notes, he quoted philosophers and poets. In his interviews, he challenged the music industry’s neglect of Latin music history. He was, in every way, a revolutionary who happened to play piano.

Chapter 5: Spirituality, Legacy, and the Afro-Caribbean Roots

You can’t truly understand Eddie Palmieri without acknowledging his deep respect for Afro-Caribbean spirituality. While never preachy, his music pulsed with sacred energy—drawing from Santería, Lucumí, and Yoruba traditions passed down through centuries of struggle and survival.

Palmieri believed in ancestral memory, and his arrangements often felt like invocations. Listen to tracks like “Bamboléate,” “Lucumi, Macumba, Voodoo,” or “Oyelo Que Te Conviene.” These aren’t just songs—they’re ceremonies. Palmieri didn’t just borrow from Afro-Cuban culture—he honored it, studied it, and wove it into his musical DNA.

That reverence extended to the musicians he chose. His bands were like sonic temples, filled with the most spiritually and technically gifted players available. Many of today’s Latin jazz luminaries got their start in Palmieri’s ensembles. For him, mentorship wasn’t a duty—it was a tradition.

And it wasn’t just Latin artists who cited him as an influence. Jazz pianists like Chucho Valdés, Danilo Pérez, and Gonzalo Rubalcaba have all acknowledged Palmieri’s impact. Even non-Latin musicians—across funk, hip-hop, and even EDM—have sampled or studied his rhythmic architecture.

Palmieri’s use of the clave, the rhythmic heartbeat of Afro-Caribbean music, was particularly profound. For him, the clave wasn’t just a timekeeper—it was a philosophy. A structure through which emotion, intellect, and improvisation could align. He often said:

“Without the clave, there is no truth in Latin music.”

That commitment to truth extended beyond the music. He was an outspoken critic of racism, gentrification, and cultural erasure. His records spoke for those unheard. And his legacy isn’t just in notes—it’s in the dignity and identity his music affirmed.

Chapter 6: The Later Years and the Circle Completed

In his later years, Eddie Palmieri could have slowed down. Instead, he dug deeper.

Albums like Ritmo Caliente (2004), Simpático (2006, with Brian Lynch), and Sabiduría (2017) revealed an artist still restless, still hungry to explore. He surrounded himself with young musicians, ensuring that the fire stayed lit. These weren’t nostalgia records—they were proof that Palmieri was always current, even when reaching back to tradition.

In 2018, he released Full Circle, an album of classic tracks re-recorded with live rhythm section and overdubbed brass—a way to revisit old triumphs with new fire. Listening to that album, you can feel the elder statesman’s pride. Not just in the tunes themselves, but in how far the music had come. How much had been built on the foundation he helped lay.

He received lifetime achievement awards, was inducted into the Latin Music Hall of Fame, and was honored by the Jazz Foundation of America. But awards were never the point. Palmieri remained fiercely independent—releasing music on his own label, touring internationally, and giving interviews filled with sharp wit, boundless energy, and cultural critique.

When he spoke publicly, he sounded more like a philosopher than a musician. He quoted Socrates, talked about vibration, energy, science, and spirituality. But sit him at a piano, and all the abstraction melted into feeling.

Even into his 80s, Palmieri played with the fire of a man half his age. Seeing him live was a spiritual experience. You’d see generations in the crowd—salsa dancers in their 70s, jazz heads in their 40s, and teenagers discovering for the first time what it meant to be moved by a groove.

And then, in August 2025, the news came: Eddie Palmieri had passed away at the age of 88.

The silence that followed was deafening.

Epilogue: A Life in Full Rhythm

Eddie Palmieri didn’t just play Latin jazz. He redefined it. He refused to let it be boxed in by commercial labels, ethnographic clichés, or industry expectations. He demanded that it be treated as art. As resistance. As memory. As a future.

He showed that you could honour tradition while pushing forward. That you could be Caribbean and cosmopolitan, scholarly and streetwise, spiritual and experimental. He showed that Latin music was not a side dish—it was a main course. A culture. A cosmos.

For me, Palmieri’s passing feels very personal. His music has been part of my life’s soundtrack. It played in the background of my most joyous memories and stood beside me in times of reflection. It reminded me that jazz isn’t just American, that rhythm isn’t just for dancing, and that truth can be told in clave.

Now, he’s gone. But the montuno continues. The clave still cracks. The spirit remains.

As long as there are pianos to pound, congas to call, and dancers ready to whirl, Eddie Palmieri will live on.

Gracias, Maestro.