Fela Kuti: The Fire That Never Went Out

In the pantheon of 20th-century musical visionaries, few figures loom as large — or burn as defiantly — as Fela Anikulapo Kuti. A sonic revolutionary, political dissident, and cultural prophet, Fela fused jazz, funk, highlife, and Yoruba rhythms into something entirely new: Afrobeat. But beyond the groove and the brass, the sweat and swagger, there was always something more urgent in his music — a call to arms, a protest in polyrhythm, a spiritual and ideological war cry wrapped in percussive rebellion.

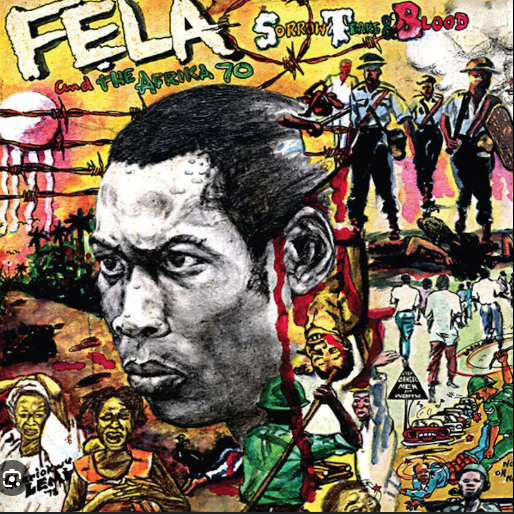

Fela’s music was never just entertainment. It was testimony. It was resistance. It was truth-telling in 12-minute movements, stretched across the hot Lagos night. With lyrics in Yoruba and pidgin English, he sang to and for the people: Nigeria’s disenfranchised, disillusioned, and determined.

Born Olufela Olusegun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti on October 15, 1938, in Abeokuta, Nigeria, his was a life destined for disruption. His mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, was a feminist, an anti-colonial campaigner, and a union organizer — a radical in her own right. His father, Reverend Israel Ransome-Kuti, was an Anglican minister and educator. That mix of progressive resistance and intellectual discipline shaped Fela’s worldview long before he ever blew a trumpet.

The Early Notes: Jazz, London, and a Search for SoundIn 1958, like many young Nigerians of his generation, Fela travelled to London. Officially, he enrolled at Trinity College of Music to study classical trumpet and composition.

Unofficially, he immersed himself in jazz, soul, and rhythm & blues — the music pulsing through the clubs and counterculture scenes of post-war Britain.He played piano in small bands and absorbed the improvisational language of jazz like a second mother tongue. He was listening to Coltrane, to Ellington, to Miles. He wasn’t just soaking up Western harmonies; he was recalibrating them through the prism of his own African experience. It wasn’t long before the seeds of something new began to take root.By the early 1960s, Fela had formed Koola Lobitos — a highlife-jazz fusion outfit blending West African guitar lines with bebop sensibilities. At first, the music was more groove than gospel, more horn charts than harangue. But everything changed in 1969.

America, Black Power, and the Awakening, During a tour of the United States, Fela spent time in Los Angeles and was deeply affected by the political atmosphere. The civil rights movement had given way to Black Power, and the underground scene buzzed with ideas, urgency, and activism. Fela found himself surrounded by thinkers, artists, and agitators, people like Sandra Smith (later Sandra Izsadore), a member of the Black Panther Party, who introduced him to the writings of Malcolm X, Kwame Nkrumah, Frantz Fanon, and the music of the Last Poets.It was an ideological awakening.

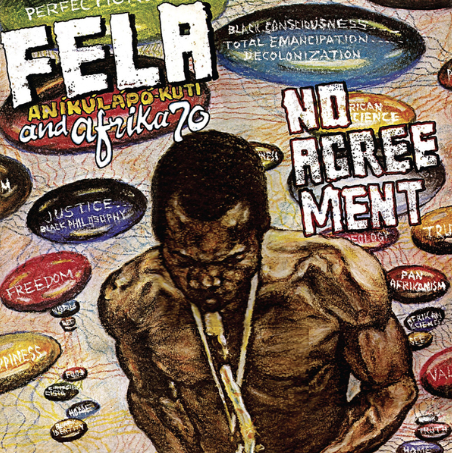

Fela returned to Nigeria with a fire in his belly and a new sense of purpose. The musical experimentation continued, but now there was something else driving it: a deep, righteous rage. He began to retool his sound into something more elastic and incendiary, polyrhythmic, horn-heavy, call-and-response driven, a new genre that would become Afrobeat. Koola Lobitos transformed into Africa 70, and the music took on sharper teeth. This wasn’t just a new band. It was a new movement, Afrobeat:

The Birth of a Language Afrobeat was never just a genre, it was a system. A live ecosystem of groove, message, dance, and confrontation. Built on the backbone of extended jams and interlocking rhythms, the songs often stretched to 10, 12, even 15 minutes, not because of indulgence, but necessity. Afrobeat was ritual, drama, and resistance in real time. The rhythm section was the engine. The horns, the voice. But at the centre was always Fela, his lean frame, shirtless and electrified, barking verses through clenched teeth or crooning through clenched truth. Every performance was a sermon. Every track was a document.

His band, first known as Nigeria 70, then Africa 70, and eventually Egypt 80, was a shifting collective of virtuosic musicians, dancers, and acolytes who lived and worked with Fela in his infamous Kalakuta Republic. This self-declared commune on the outskirts of Lagos was both sanctuary and stage: a space where music, ideology, and daily life collided, clashed, and combusted.

Fire on the Needle: Essential Albums.

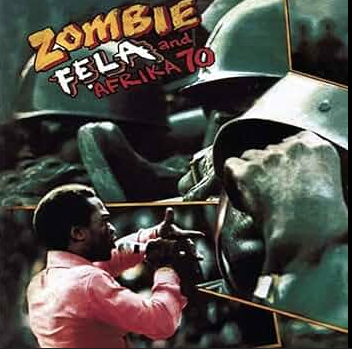

1. Zombie (1976)No Fela retrospective is complete without Zombie. Perhaps his most politically explosive work, the title track is a scathing satire of Nigeria’s military, likening soldiers to mindless “zombies” obeying orders without thought. It was bold, direct, and devastating.The regime did not take it lightly. In 1977, in retaliation for the song and Fela’s increasing outspokenness, government forces attacked the Kalakuta Republic. They burned the compound to the ground. Fela was beaten. His mother, thrown from a window, later died from her injuries. But Fela didn’t go silent. He responded by delivering his mother’s coffin to a military barracks and releasing the song “Coffin for Head of State.” He would never relent.

2. Expensive Shit (1975)Equally legendary is Expensive Shit, an album born of one of the most bizarre incidents in musical history. After police planted marijuana in his home, Fela swallowed the evidence. Authorities held him until he could produce a stool sample. When he outwitted them (via a substitution trick), he emerged uncharged and inspired.The track “Expensive Shit” turns this entire episode into raw art, a swaggering, bass-heavy groove punctuated by mocking horns and biting social commentary. It's defiant, funky, and quintessentially Fela.

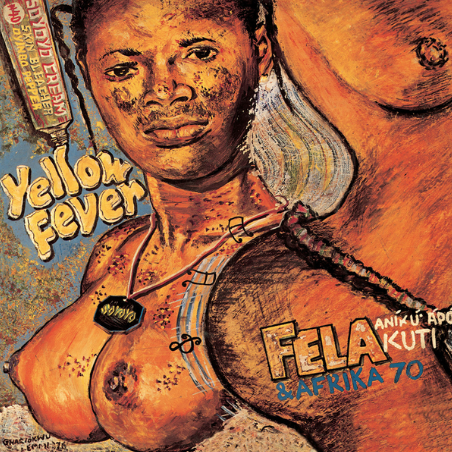

3. Shakara (1972)On Shakara, Fela leans into both satire and sensuality. The title track playfully skewers male arrogance and social posturing, while “Lady” — one of his most discussed (and critiqued) songs targets Western feminism from a uniquely Nigerian male perspective.While some have argued that “Lady” reflects outdated gender views, it’s also a window into Fela’s own contradictions, as a man born of a feminist mother who often clashed with progressive women, even as he championed liberation in other forms. Musically, the album is tight and hypnotic, the horns glide, the percussion stings, and the groove never lets go.

4. Roforofo Fight (1972)A thunderous slab of early Afrobeat. The 15-minute title track is a showcase of Fela’s storytelling, about a petty street fight that becomes an allegory for broader chaos and hypocrisy. It’s street-level observation elevated to parable, set to a relentless rhythm that simmers and surges.Roforofo means "mud" in Yoruba, and the fight unfolds in it physically and metaphorically. By the time the track ends, you’re not just listening to music; you’re witnessing theatre.

Kalakuta Republic and the Cult of FelaFela’s compound Kalakuta Republic, functioned as his personal nation-state. It had its own rules, its own economy, and its own ethos. There, he lived with his family, his band, and his many wives (he famously married 27 women in a single ceremony in 1978). It was a commune, a laboratory, and a pressure cooker.To some, Kalakuta was a symbol of freedom, creativity, and African self-determination. To others, it was chaotic and controversial, an indulgent cult of personality wrapped in ganja smoke and political provocation. The truth probably lies somewhere in between. What is certain is that it was a direct affront to Nigeria’s military establishment, and they knew it.

Fela’s nightclub, the Shrine, became the epicentre of Lagos nightlife and political discourse. His shows ran into the early hours, soaked in sweat, sound, and sermon. The Shrine wasn’t just a venue. It was a parliament.

Jail, Politics, and the Cost of DissentFela’s run-ins with the law were frequent and often brutal. In 1984, under the military dictatorship of Muhammadu Buhari, he was sentenced to 20 months in prison on trumped-up currency smuggling charges. Amnesty International named him a prisoner of conscience, and pressure mounted until his release in 1985. He returned to music not mellowed, but even more furious. In 1993, he was arrested again, this time on murder charges, which were later dropped. Through it all, he never stopped recording, never stopped performing, never stopped speaking truth.

In 1979, Fela even tried to run for president under the banner of his own political party, the Movement of the People. He was rejected by the electoral commission, but the gesture was emblematic of his refusal to simply play by the rules. He was never going to be silenced.

Death and Legacy: A Flame Passed Down, Fela Kuti died on August 2, 1997, from complications related to AIDS. He was 58. His funeral drew more than a million mourners in Lagos, a final testament to the depth of his impact, not just as an artist, but as a cultural force.In death, his myth only grew. His son, Femi Kuti, and later his grandson, Made Kuti, have both carried the Afrobeat tradition forward, injecting their own voices and ideas into a sound built on rebellion and groove.

But no one not even his children has matched the raw force of Fela.His music has been sampled by hip-hop producers, reissued by labels like Knitting Factory and Partisan Records, and staged in Broadway musicals like Fela!. His political ideas — Pan-Africanism, anti-imperialism, and radical self-expression, remain as relevant as ever.

Today, Fela Kuti is more than a genre pioneer. He’s a lens through which we understand the power of sound as resistance, rhythm as rhetoric, and music as the living archive of a people’s struggle.

Final Thoughts: The Beat Goes OnFela’s music wasn’t made for nostalgia. It was made to be played loud. It was made to be danced to, debated over, studied, and shouted. His legacy lives in every beat-driven protest, in every independent musician who chooses message over mainstream, in every artist who dares to speak truth to power.Afrobeat is more than a sound now. It’s a stance. And Fela whether lighting up the Shrine at 2 a.m. or spitting fire into a battered microphone, is still very much here. The sax may be silent. But the message? It's eternal.